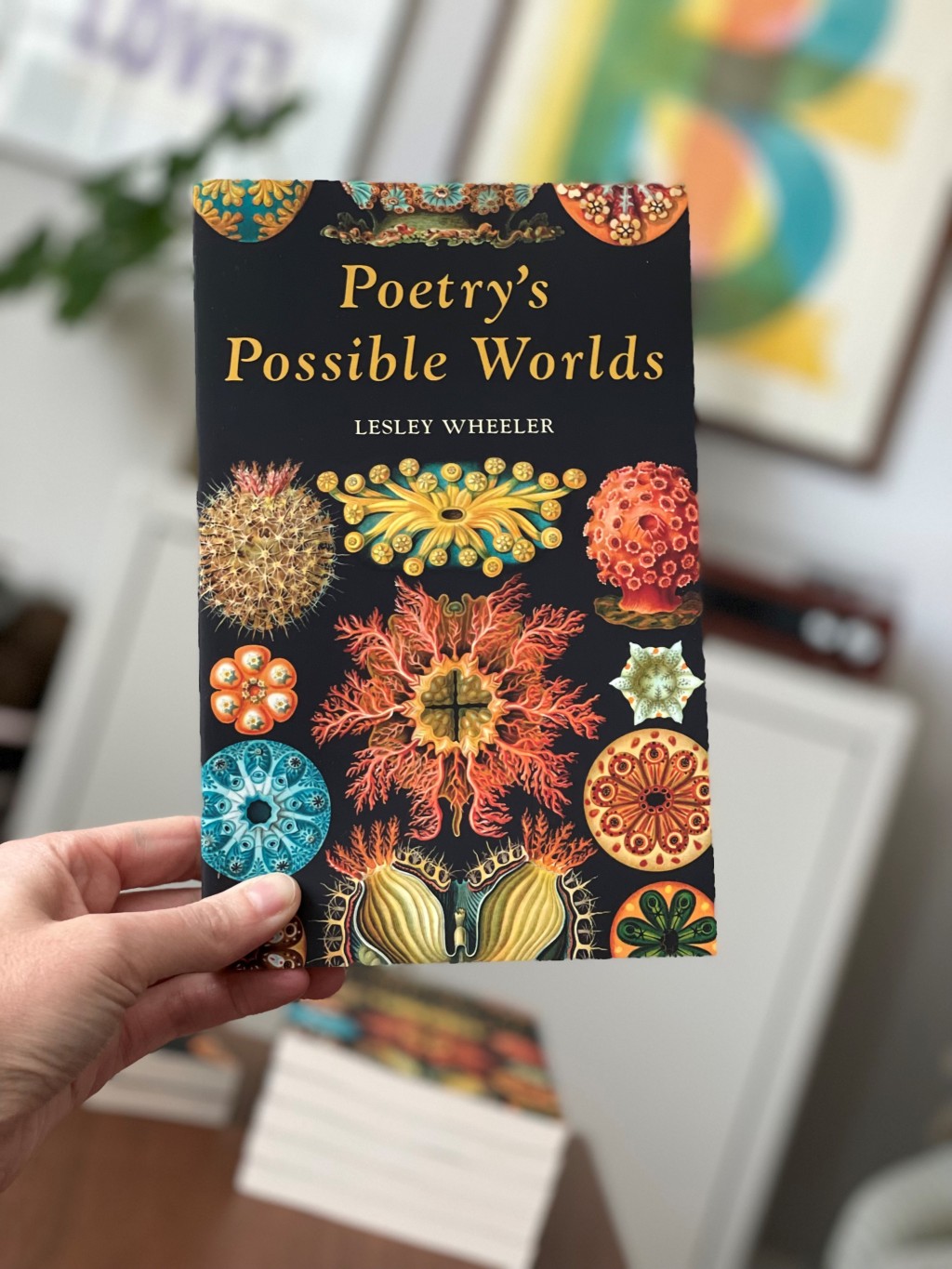

Poetry’s Possible Worlds emerged from years of teaching undergraduates who don’t believe that learning how to write academic essays about literature has long-term relevance to their lives. Many of my students, though, enjoy–or can be surprised into enjoying–reading, thinking, and talking about books and poems, so the puzzle has been: how do I make writing assignments seem as intrinsically interesting as class discussion? I can argue sincerely that applying critical intelligence to an ambiguous text stretches the mind and spirit in rewarding ways; knowing how to assemble a persuasive argument backed by evidence is an incredibly useful and widely applicable skill; related practices, especially the ability to conduct research and evaluate sources, are also valuable lifelong, in many contexts; and that you only get better at writing by practicing a LOT (think Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hour rule). They may believe me, but these rational arguments wouldn’t make most people want to write an academic essay (although there are exceptions!). One way I’ve been trying to make writing criticism more pleasurable for students–and for me–is by raising the personal stakes, as in Poetry’s Possible Worlds: for example, I give students the option of connecting a poem to their own struggles, bringing emotion to bear on well-informed analysis. This absolutely does increase student enthusiasm–and also, often, the verve of the writing, making a grader’s job more fun.

But now comes a paradigm shift. Generative AI tools are quite capable of producing memoir as well as many other kinds of prose (you could ask ChatGPT to relate a poem to your grief about your dead dog, for example). Connecting assignments to big life questions remains a great pedagogical move–it increases students’ motivation to do hard work–but powerful writing tools are still just sitting there, and plagiarism policies aside, you haven’t given them an intrinsic reason not to use them.

Deterring cheating is only a small part of the picture. I want to empower the humans in my classes to live rich lives and do good work in the world long after their formal schooling ends. Their employers will almost certainly expect judicious AI use on the job for some writing tasks–“judicious” being the key. I should help prepare students for that, as I used to prepare them for different writing conditions. As my spouse says, these tools are “mediocrity machines”: what they produce is bland, vague, full of bogus evidence, and inherently plagiaristic (AI doesn’t cite sources). But as others have observed, generative AI tools can still be useful at many stages of writing in many genres, including brainstorming, outlining, and revision. If I pretend they don’t exist, I’ll rightly lose student confidence from the get-go.

Generative AI has plenty of limits. I’m far from the first to demonstrate that asking ChatGPT or Bard to write a poem produces swill. By way of example, if you ask ChatGPT to rewrite my recently published poem “Message from the Next Life”, this happens:

"Echoes from Beyond for Beth A call from the far side of a crimson bridge, Where sleep eludes with steel embrace, Once named "bludge," now whispered as "broodge," River's voice moody, in softened grace. A heat-flash of thoughts, a twist of fate, Flesh and time entwined, like rust's embrace, Apologies for the shadows cast, Though appearances falter, beauty's traced. Where once a meadow thrived with glee, Mockingbirds' songs and meteors' dance, Now cat's-cradle cables obscure the scene, Yet memories breathe, in a hopeful trance. Beth, dear friend of shared memories past, A journey made to an unknown shore, In dreams, a child that was never cast, Whispers in brain-beams, forevermore. With strength we forge a bridge anew, Swinging, swaying in a dance of luck, We'll craft a wish, woven and true, For fate to rhyme and serendipity pluck. A sleepless message, in time's embrace, An offering of dreams, a gift sublime, Delivered by heartbeats, through time and space, A fragment of hope in the grand design." Ick. You'd have to transform the language substantially, through erasure or a similar procedure, to re-engineer something decent. But if I ask ChatGPT to ask me questions about the poem, I get a non-insane list that looks like a paper prompt or lesson plan:

“Here are some questions to help us delve into the poem’s meaning and elements:

- Title and Dedication:

- What significance might the title “MESSAGE FROM THE NEXT LIFE for Beth” have for the poem?

- Who do you think Beth might be, and why might the poem be dedicated to her?

- Imagery and Language:

- The poem mentions a “blood-bridge” and “steel-girdered insomnia.” What do you interpret these phrases to mean, and how do they contribute to the overall atmosphere of the poem?

- The term “bludge” is introduced as a shortening of “blood-bridge.” What does this neologism suggest?

- The word “broodge” is used instead of “bludge” later in the poem. How does this change in language affect the mood and imagery?

- The poem uses words like “hotflash,” “misindirection,” “fleshiness,” and “rust.” How do these sensory and tactile descriptions contribute to the reader’s understanding?

- Description of Setting:

- What is the significance of the pier and the river mentioned in the poem? How do they relate to the themes and emotions presented?

- The poem contrasts the narrator’s memory of a meadow with the current view. How does this contrast contribute to the sense of loss or change?

- Implied Narrative:

- The narrator mentions a “third baby I never bore.” What do you think the significance of this unborn child might be? How does it connect to the theme of the poem?

- The line “They talk to me in brain-beams” introduces an element of the supernatural. How does this line contribute to the mysterious and otherworldly feeling of the poem?

- Tone and Emotion:

- How would you describe the overall tone of the poem? Is it melancholic, hopeful, or something else?

- How do the phrases “we’ll put our backs into budging your luck” and “Let fate rhyme a smidge of wish into a sleepless package” contribute to the sense of determination and connection?

- Structure and Wordplay:

- The poem contains playful language, like “sweck,” “derve,” and “recombinating.” What effect do these playful language inventions have on the poem’s meaning and tone?

- Themes:

- What themes do you think the poem explores? Love, memory, connection with the beyond, or something else?

Remember, these questions are meant to guide your analysis and understanding of the poem. Feel free to explore any aspects that resonate with you, and share your thoughts on the imagery, language, emotions, and themes presented in the poem.”

Teaching “Message from the Next Life” (not that I would teach my own poem), I’d certainly ask some of these questions–about the neologisms (after explaining that word); the significance of the poem having a dedicatee; and the supernatural element. ChatGPT misses much that’s fundamental, including the poem’s central wish that a friend who’s struggling with fertility will bear a child–I intended it as a kind of spell–but when I asked for an essay about the poem, ChatGPT produced a paragraph getting at this element:

“As the poem progresses, the determination to influence fate emerges. The narrator and the “they” who speak in “brain-beams” become active agents in crafting a wish. The metaphor of “putting our backs into budging your luck” conveys a sense of collaborative effort to transcend the limitations of circumstance. The act of “fate rhyme[ing] a smidge of wish into a sleepless package” implies an intricate weaving of hope and destiny, culminating in a timeless, sleepless message.”

“Timeless, sleepless message”: also, ick. Play with these tools a while, and you begin to recognize a pretentious, generalizing style that’s heavy on ecstatic adjectives. There’s no formal analysis in the ChatGPT essay, either; this is an irregular sonnet, a detail I consider pretty relevant. But the essay as a whole is fluently written, logically organized, and full of plausible points. Honestly, many first-years even at a highly selective college struggle to hit that baseline.

In fact, asking an AI tool to write an essay (or blog post) about a poem works better than asking for the same about a novel. If you can’t feed in the whole text, ChatGPT “hallucinates” evidence including, if you nudge it for textual analysis, atrociously fictitious quotes that a half-conscious teacher would instantly recognize as not part of the original. But cutting and pasting a short piece, such as a poem, into the query slot is easy and results in accurate quotations. The essay ChatGPT generated for me even noted a mix of abstract and concrete nouns in one of my lines–from a first-year writing student, that would impress me.

My initial reaction, as I consumed the past year’s flood of articles about AI writing, was that I’d explicitly forbid the tool’s use from here on in. Forget it, and done. I discussed the issue with my spring class right after handing graded papers back, because another colleague had identified a student’s paper submissions as AI-generated (via hallucinated evidence). We have a strict honor code and people here are pretty interested in these questions: did they think this practice was frequent or should ever be permissible? Without a teacher’s permission, unethical, they said. They also reported that some professors in non-writing-focused disciplines were advising students to use ChatGPT. Then one student who’d submitted a vague but grammatically accurate paper about a novel–it used precious little textual evidence, so it earned a weak but passing grade–dropped the class. I barely had time to think about it during the term; now I suspect that the essay was AI-generated, although in the absence of clear policies from me, the student may not have understood that process as cheating until our class discussion. In any case, even in a school some attend because of the honor system and a presumption of trust among faculty and students, the cat is out of the bag.

Then despair and exhaustion really hit. I’ve spent (timeless, sleepless) decades learning how to teach writing effectively. Now I had to reinvent everything? The main thing I could foresee was more unpaid work ahead and an absence of university policy (both accurate predictions so far–if W&L’s honor code orientation will address AI tools, no one has mentioned how to the faculty). I felt bad for the whole profession, knowing that plenty of professors are more burnt out and less well-remunerated than I am.

AI-generated short stories were also bombarding SF magazines, which made me wonder about professional as well as student use of generative AI. For example, an overworked writing teacher can now ask these tools to grade papers and write explanatory comments about the grade. When I experimented with this, ChatGPT gave its own essay about “Message from the Next Life” an A-, praising the essay’s insight and structure but recommending more textual analysis. These tools can also produce syllabi, recommendation letters, and a host of other professional documents. More reasons for policies.

Then I reminded myself about other paradigm shifts my teaching has survived. When I arrived at W&L in 1994, administrators’ memos still arrived on paper and there was no encyclopedia or search engine to consult, say, about a 1950s pop culture reference in a poem. ChatGPT isn’t more revolutionary than the Internet. For that matter, I’ll spend the rest of my career teaching people who were teens or little kids during the pandemic, who lost social and academic skills and are sometimes outraged that I count missed classes against their averages. To teach is to pivot. I like that about my job, mostly.

My fall plan is mainly to keep talking about these tools with my classes; generate short AI essays from my writing prompts and critique them in class together; try using ChatGPT to outline or make suggestions about what they’ve already written and see whether this exercise helps them revise; and to be both very clear and open-minded about ground rules, as students show me ways of using these tools that I may not have imagined. Poetry writing teachers have a brief respite, given the current poem=doggerel equation, but AI will catch up; it’s already possible to write a passable short story draft with ChatGPT, as the aforementioned spouse, Chris Gavaler, shows in this post and its sequels.

I remain worried about the students who struggle to write clear sentences. Now they can dump a draft in a query box and emerge with something pretty. Is that a great equalizer, enabling them to succeed and me to focus more wholly on the quality of their reasoning? Can they learn what they need to know by examining how AI “fixes” their writing? Or do they struggle with how to punctuate for the rest of their lives, needing to run every single email they write through an editing program, when in a previous world coursework might have nudged them to learn the rules?

Some good results I anticipate: literature and writing teachers will have to think hard about why we read and write, and how those reasons should inform what we teach. A sense of intimacy with other human minds via their personally chosen words will become even more electrifying. And easy generalizations about challenging texts will never again pass muster among anyone who is paying attention.

8 responses to “Writing about poetry with AI”

I was recently asked to edit a “scholarly article” so dreadful and cringe-worthy it could only have been AI generated. A publisher sent it as a freelance copy editing test (!) but it took considerably longer to mark up than a piece of that length should. One of the few quotes in the article was from *a review* of the book cited in the end notes rather than the book itself, and several additional sentences from that same review had been used without quotation. I decided these were people I did not want to work for.

I’m glad you are approaching this thoughtfully and pragmatically rather than with the knee-jerk panic seen in some quarters. What an excellent teacher you are! Your students are terribly lucky to have you. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! And about that editing assignment: WHOA. Right–not a potential employer with good judgment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

these tools are “mediocrity machines” <– YES! I tell this to people over and over again. It's a statistical average of writing and information. Average=not above average.

Also this: "The main thing I could foresee was more unpaid work ahead and an absence of university policy (both accurate predictions so far–if W&L’s honor code orientation will address AI tools, no one has mentioned how to the faculty)." The college from which I so recently retired seemed unwilling or unable to address AI in an across-curriculum manner, partly because we have so many students in business-related and medical-business-related majors (and those people, once in the workforce, will be expected to know how to use AI efficiently).

Furthermore, as the person running the writing center–though not faculty–I could see myself being drafted into unpaid and possibly stressful work on this topic and, likely as not, making relatively little difference. Sorry to be cynical, but it seemed a good time to retire from academia.

I still find AI to be a really intriguing tool and suspect that in a few years, we'll treat it much as we now treat Wikipedia, which was considered a threat to academia and learning when it first arrived on the scene.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Honestly, one of my first thoughts was “can I retire yet?” I’m glad you could! And yes, we have a lot of business-oriented students, too: “liberal arts college with a business school” is pretty much our brand. Finally, what you say about Wikipedia sounds right to me–ultimately the latter helps me, although learning its strengths and limits took a while. The for-profit model of ChatGPT is an interesting difference, though.

LikeLike

Lots of intriguing thoughts in this post today. Poetry’s Possible Worlds has reinforced my tendency to break further from the New Criticism tradition of my mid-century teachers and to then explain my impressions of poetry as acts of fellow, particular people. In this I feel different from my teenager, who alternates between Death of the Author and rejection of the work based on sins and stupidity of the author.

Still, AI in art is easier for me to parse than your job of considering AI in education.

Wishing you best of luck on your upcoming school year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Frank!

LikeLiked by 1 person

“As the story progresses” to “As the narrative unfolds” irks me no end. In another application: a friend sent me a poem, proudly announcing that she had asked AI to write a Diane Kendig poem. I was appalled. It was all simple sentences, most in the imperative, on the subject of…rocks– none of which I could find in any of my poems.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh good lord! I’m scared to ask that “write in the style of” question, but since the poems it produces are terrible, you could ask some version of “tell me about Diane Kendig’s writing.” I wonder what it would come up with?

LikeLike