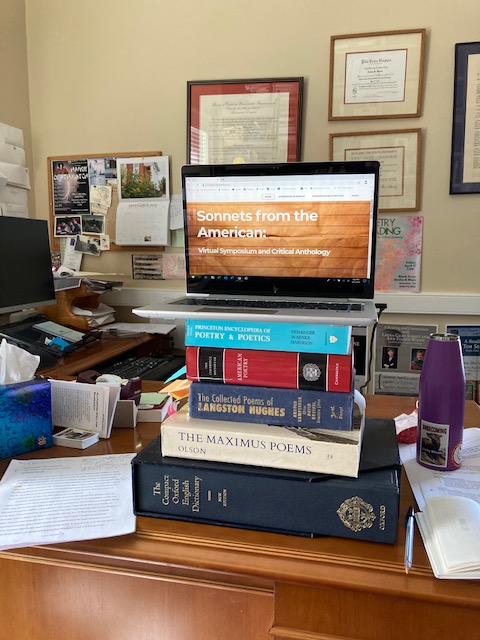

Octave and sestet: my ridiculously precarious Zoom setup for delivering a paper at the Sonnets from the American Symposium, and then my home symposium-delivery system. Presenting on short-lined sonnets in a piece called “Partial Visibility,” I edited my messy desk out of the virtual window, throwing the focus instead on the bookcases behind me–so much more professorial. I thought about our partial visibility to each other all weekend, especially when Diane Seuss, the second-lo-last reader in the final event, talked about using long lines to expand the parts of life that can be included in the sonnet’s “gilded frame.” (Her new book, frank: sonnets, promises to be amazing.)

I loved the symposium, which was thoughtfully and effectively curated, and I learned a lot. Among the highlights: we viewed a video tribute to Wanda Coleman and her American sonnets put together by Terrance Hayes. There were mesmerizing live readings by Rosebud Ben-Oni, Kazim Ali, Tacey Atsitty, Kiki Petrosino, Shane McRae, Patricia Smith, and many others. Carl Phillips gave a particularly good keynote about “disruption built into” the sonnet and its “tendency to sonic dispersion,” making the form especially hospitable to marginalized writers. Fruitful panel discussions swirled around work by Claude McKay, Gwendolyn Brooks, Jericho Brown, Brandi McDougall, Henri Cole, and many more. I heard from friends, put some names and faces together among scholars and poets I knew only by reputation, and even saw fellow bloggers whom I’d never before met (hello, Frank Hudson! I really appreciated your comments and want to hear more about singing sonnets sometime). What I liked best were the recurrent readings of the American sonnet as a dissident form, incorporating multiple voices through its characteristic turns and pivots, treated rebelliously and inventively by North American practitioners. When Phillips called the sonnet “wired for rebellion,” he echoed the symposium’s exhilarating theme–exhilarating for me, anyway, because my education emphasized the sonnet as an exercise in obedience.

This symposium also gave me a million ideas for writing. I gave you a prompt for short-lined sonnets last week as I was prepping my paper. Here are some more, with credit to the presenters who jogged these ideas.

Interpreting the parameters of the form however you like, write a sonnet that:

- Is a mode of transport or place of collision (Marlo Starr, “Dissident Sonnets”; Yuki Tanaka, “Cross-Cultural Sonnets”)

- Depends on a single repeated line, like “Nothing in That Drawer” by Ron Padgett, possibly breaking the pattern at the end (Rebecca Morgan Frank, “Standing In One Place to Move”)

- Involves collaboration, maybe tossing couplets back and forth with a partner or using octave/sestet for the switch between voices (Simone Muench and Jackie K. White, “The Sonnet as Conversation”). (I’ve been involved, too, in a couple of collaborative crowns, handing off the baton poem by poem. Here’s one.)

- Uses a meter other than iambic, as Courtney Lamar Charleston does in “Doppelgangbanger” (Anna Lena Phillips Bell, “This resonant, strange, vaulting roof’”)

- Is a duplex, following Jericho Brown’s torque of the form (Michael Dumanis, “Subverting the Tradition in The Tradition”)

- Is improvisatory, derived from jazz, a mode Brian Teare discussed in relation to Wanda Coleman (I think this was in post-panel chat–but if you want to read more Coleman than the “American Sonnet” I just linked to, I highly recommend the new Selected Poems edited by Hayes)

- Is based on David Wojahn’s “rock n roll sonnets,” Molly Peacock’s “exploded sonnets,” Tyehimba Jess’ “syncopated sonnets,” Philip Metres’ “shrapnel sonnets,” Amit Majmudar’s “sonzal,” Lyn Hejinian’s “anti-sonnets”–research these variants and have at ’em! (Kevin McFadden, “The Resistant Strain,” plus additions from the chat after)

- Dances through the volta in an unusual way. Many panels raised these questions: where can voltas go? Can they be outside poems, or between poems in a sequence?

- Breaks other “rules.” A prompt for any form: what patterns can you warp to put your work in lively conversation with the myriad traditions snaking behind us? Or, how can you hybridize sonnets with other forms or texts, as poets do with blues sonnets and sonnet-ballads?

I hope one of those prompts clicks for you and you start drafting. We can’t doomscroll ALL the time (hey, what would a doomscrolling sonnet look like?). For still more alternatives to watching the political weather, check out this cool cluster of short essays, “#MeToo and Modernism,” just published by Modernism/ modernity; I have a piece in there about teaching Eliot recruited after the editor saw my blog post on that subject–an interesting development that has now happened to me a couple of times. And if you’d be up to listen in on an intimate multipoet reading from 6-7pm ET on Thursday 10/15, please contact me and I’ll send you the link. It’s part of a sweetly inclusive series run by Lucy Bucknell at Hopkins, not fully public, but I’m allowed to invite friends.

5 responses to “Sonnet prompts from #SonnetsfromtheAmerican”

What a wealth! Thank you, Leslie. As Molly Peacock once said, the sonnet is (or can be) the emergency form. Doomscrolling begone!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I should write a post myself on how much I too enjoyed that American Sonnets conference. I thank you so much for letting me know of that event. One over-riding impression for me: it made me comfortable that American poets are happy to reinvent/reinvigorate the sonnet form.

Your post asks a couple of questions. Let me embarrass myself by responding as I too often do by going on too long.

Challenges to singing sonnets? What I was too briefly suggesting this week is that unlike many other lyric poetry forms, sonnet writers often eschew repetition and refrain. Hey, it’s a compressed art, don’t waste words, poets think. Music can work easily with strophic effects, but they’re often missing—so even though they’re short, most sonnets suggest their musical setting be “through composed.” Art Song musical traditions are comfortable with through composed, but I work often from a folk-music background that commonly uses refrain (something I didn’t see yet in “Ballad Sonnets” I learned about from this conference—more to find out there). So even the barest use of refrain helps something like Dunbar’s “We Wear the Mask” get into a friendly “song” as opposed to Art Song format.

Modern commercial music is even more addicted to repetition. So, when folks try to sing even rhyming and metrical sonnets there’s a burden there for audiences with those expectations.

As to a Doom Scrolling sonnet, here’s the next draft of that free verse one with an ever-increasing stanza length I’ve been working on. It begs for a paired sonnet that reverses the increase—to instead decrease by one line each stanza to a sonnet-signaling final couplet.

Doom Scrolling

The picture, not yet in the camera,

Asks to be let in, where it cannot breathe.

A committee of birds meets, decides it’s fall,

Stays, then freezes in December.

Long feathers stiffen in loose snowflakes.

Half the country says darkness doesn’t exist

Because they cannot see it—

And half says the daylight is too short

To see enough at all.

Since there are too many links to find the way,

And this, like any distressing path, is not straightforward,

Expect that you are lost.

Can you bless, what you come upon twice,

Though it shows: you haven’t gone as far as hoped?

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Lesley Wheeler, Sonnet prompts from #SonnetsfromtheAmerican […]

LikeLike

It’s interesting that your sonnet might not be visible as piece about reading online without the title–it really concretizes (if that’s a word?) abstractions in seasonal imagery. The second-to-last stanza works particularly well for me, maybe because the quatrain resonates so much with its content of doubleness.

And yeah, your general point about unsing-able compression makes a lot of sense to me. That has something to do with print culture, I think. I know that when I write more loosely, with repetition and more room to breathe, a poem is less likely to work for journal editors. Either the 21st c canon-makers or the medium itself likes density and difficulty (probably both). Which implies, in turn, that older poems would be easier to put to music than newer ones?

LikeLike

The event sounds wonderful–and definitely brought you inspiration. I’ve experimented with “breaking the rules” of forms, including the sonnet, in years past but not much recently; now I feel encouraged to do more in that vein. Particularly with regard to compression. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person