One relatively rare variation on the sonnet form involves very short lines. Meter may be faintly present or not at all in these poems, but line number/ structure/ rhyme look familiar. I’ve always loved Elizabeth Bishop’s “Sonnet,” a poem in this mode written late in her career and published in the New Yorker three weeks after her death in 1979.

Caught—the bubble a in the spirit level, a a creature divided; b and the compass needle a wobbling and wavering, c undecided. b Freed—the broken c thermometer's mercury d running away; e and the rainbow-bird d from the narrow bevel a of the empty mirror, d flying wherever d it feels like, gay! e

The end rhyme is sometimes so slant that my way of marking it above could trigger fisticuffs among Bishop scholars. Less arguable is the structure: that “Caught–“/ “Freed–” parallelism marks the poem’s similarity to Petrarchan sonnets, in which an octave sets out a problem and a sestet develops or resolves it. Bishop inverts that scheme, arranging a turn after the first 6 lines. Bishop sometimes used “inversion,” a sexology term indicating gender role reversal, to encode what readers might now call queerness. The structure, that is, complements imagery of coming out of the closet. The great loves of Bishop’s life were women, not something she could be open about for most of her career.

I’ve taught this poem many times so I know there’s a lot more to say–a discussion of it can run QUITE a while. I’ve been revisiting “Sonnet” this week, though, as I prepare a short paper for a virtual symposium on the weekend of October 2nd, Sonnets from the American. I linked to the “schedule” page hoping you’ll check out how many amazing people are reading and speaking: Rosebud Ben-Oni, Kazim Ali, Meg Day, Kiki Petrosino, Diane Seuss, Patricia Smith, and many more. And it’s FREE–you just have to register. I’m a little worried about Zoom stamina–I don’t really want to miss any of it, but it’s a very full 2+ days! Still, I like the tight focus of this event and, more generally, I’m glad for these little intervals of literary community.

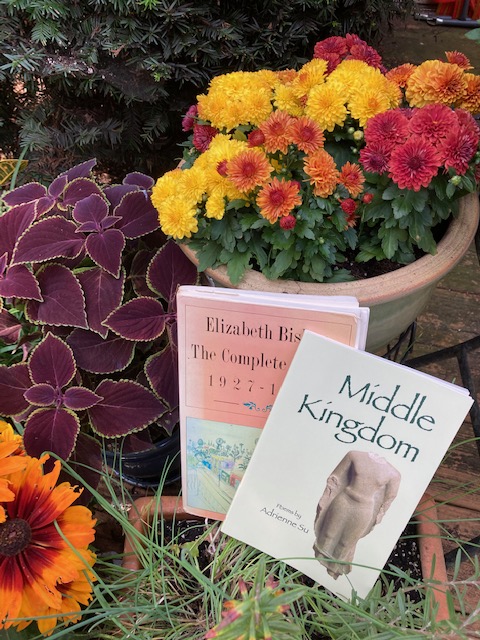

My paper will also cover a sequence by Adrienne Su, “Four Sonnets About Food.” I just read the book they’re collected in, Middle Kingdom, and spending time with it deepened my admiration of Su’s work, which is fabulous. Su’s short-lined poems follow a Shakespearean rhyme scheme and her metaphors are different than Bishop’s, but again, her deviation from the form actually seems MORE virtuoso than adhering to formula. Compression heats the lines to a boiling point.

An even tighter variation on the sonnet exists. Seymour Mayne calls it the “word sonnet”, but while I think they’re lovely, his work just isn’t in conversation with the sonnet form the way Su and Bishop are (Mayne’s word sonnets feel much more like haiku). I wrote my own sonnet with one-word lines, after many tries, but keeping the rhyme scheme; it’s in The State She’s In and also included below. I ended up calling the form “occluded” because I wanted to draw attention to what was missing. Being so looked at as a young woman made me intensely uncomfortable, but the way middle age brings invisibility wasn’t entirely welcome either. Maybe that’s a turn behind rather than within the poem.

I write sonnets so often that I joke about having a sonnet problem; my words will suddenly start slant-rhyming on me then I’m riding the volta and grabbing at closure perhaps sooner than is always good for the work. But it’s fun to experiment with a form that so many people recognize because of all the conversations it raises, AND the rebellions it makes possible (and visible). It’s also fun to turn my mind to a small critical problem like this one after swimming in a novel draft all summer. Smallness can be a respite, a way of organizing attention that otherwise keeps wandering toward the political horrorshow.

I voted early at the local registrar’s office the other day, another small good thing. Writing prompt: vote (if you’re in the U.S.), then compose a fourteen-line poem about voting. It doesn’t have to use meter or rhyme, but make sure it contains a volta around line nine, a turn toward something better.

Occulted Sonnet You look, crook head awry to elude my gaze. Nobody sees me, these days.

6 responses to “Short-lined sonnets”

Thank you so much for mentioning this symposium! I am now looking forward to attending 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yay!

LikeLike

Love the challenge of the one word sonnet, and your example–but yes, I agree, one doesn’t experience it as a sonnet, even if it (intellectually?) references it.

I fell in love with the sonnet from the 16th century English ones,* and for awhile was all iambs and rhyme schemes. But then I went on for decades thinking of every different way to factor 14 lines. For example, I just finished a decent draft of a free-verse sonnet that is 2, 3, 4 and then 5 line stanzas, and the reverse of that increase would be good too, and that would even allow for a nice rhyming couplet at the end that would immediately sound “sonnet.”

That symposium looks promising. I can see several I’d hate to miss from the promising titles.

*I still think Wyatt’s “They flee from me” is about as perfect a sonnet as has ever been written.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mayne’s are actually 14 words too–sorry to be unclear! They’re not rhymed, though, and no volta. https://jacket2.org/commentary/seymour-mayne-%E2%80%93-hail-15-word-sonnets#:~:text=The%20word%20sonnet%20is%20a,sentences%2C%20as%20the%20articulation%20requires.

I love weird rhyme arrangements. Paula Meehan has written some that rhyme abcdefg abcdefg. That’s about as much as you can hide the scheme, which is another interesting way of testing limits. It’s just a really fun form, surprisingly malleable.

LikeLike

[…] Lesley Wheeler, Short-lined sonnets […]

LikeLike

[…] symposium also gave me a million ideas for writing. I gave you a prompt for short-lined sonnets last week as I was prepping my paper. Here are some more, with credit to the presenters who jogged […]

LikeLike