The Burren

Sometimes you bring pain along like a wallet

of funny-colored bills or a mobile phone.

Here’s a knotted neck for the Burren. A spirit-

fissure to echo the limestone grykes. Karst

pavement matches you: riven grays, white lichen,

sky pale with tiredness. Stand on a clint and become

invisible, perfectly camouflaged by pain.

Yet in the watery gaps tiny pink flowers bloom,

and ferns that consider uncurling. Fisted buds open

in the cloudy light—a hand finally relaxed.

Sometimes people die, kind fathers, damaged

fathers, and you carry it around, a bottle of water

that tastes bad but you’re thirsty and must drink.

A heavy guidebook, effusive about the region

but useless on the particulars. Some burdens

lighten gradually, lost or consumed, turned into gifts.

Some you can just put down. This is a good

place for walking. Getting from island to island

absorbs all your attention. Hop from a rounded stone

to a flat one without crushing an orchid or

twisting an ankle, move across a whole field

like this, away from the portal tomb, the sad bones.

“The Burren” was published more than ten years ago in Hampden-Sydney Review, then in my 2015 collection Radioland. I fell in love with the Burren, a karst landscape in the west of Ireland, not far from Galway, during my first trip to that country, and something about the stark beauty of the place helped me move from angry poems about my father’s death to a more peaceful one.

That was a gray, cold June day; on a brilliant August one, the last day of our recent, second trip to Ireland, we revisited the place. In 2025 certain locations, especially the Poulnabrone portal tomb, are much more heavily touristed (I can’t remember it being roped off before). Wildflowers bloomed everywhere, though, and there were lots of quiet places, too. We dodged and hopped through a field of cow poop, for instance, to climb down to the ruins of a twelfth-century church, where a couple of people had tied red rags on trees in hope of healing or some other magic: an ash, a hawthorn. I can’t take long hikes at the moment, between the sprained ankle and sciatica, but I was in good enough shape for short walks, and they were again restorative.

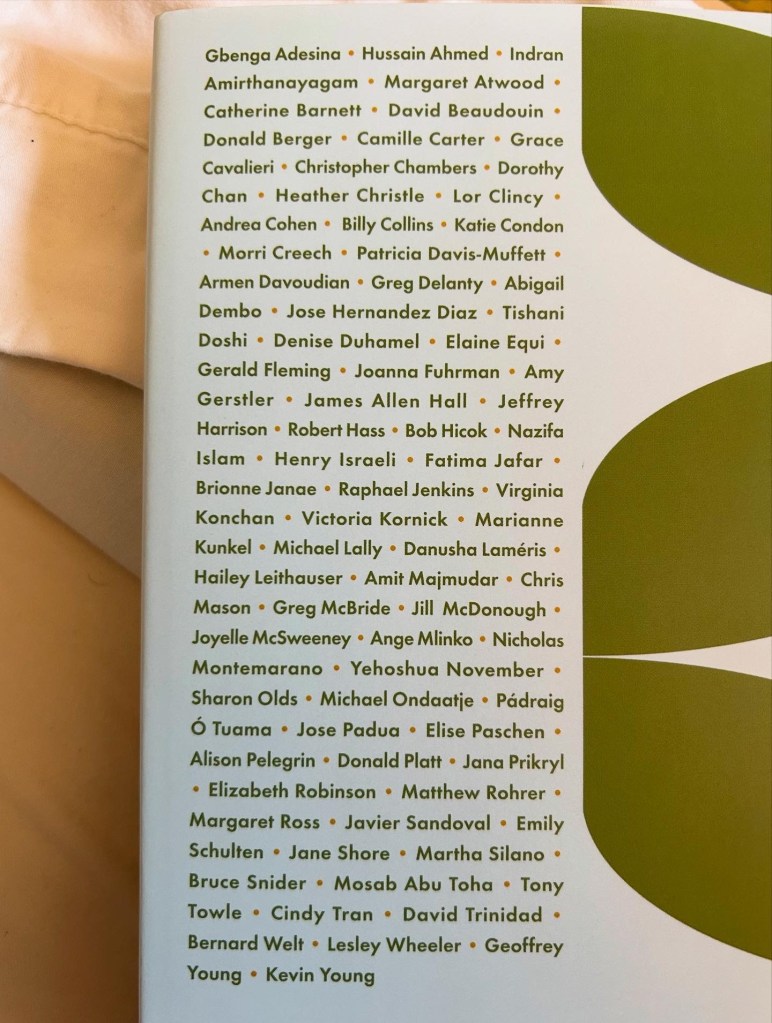

I came home from Ireland to two contributor copies of Best American Poetry 2025 and read the anthology in bed, mildly sick (I mask on planes, but apparently I picked this up before the flight, somehow–I felt the bug advancing through every tray of bad airplane food. I’m fine now, and generally better for the rest and quiet.) It’s full of powerful poems, and the variety made me happy–different career stages and levels of renown, certainly. I had thought I’d never make it into one of these collections, so the acceptance was an especially lovely surprise.

Eventually I picked up my laptop, finished writing a couple of interviews, bushwhacked my email, and thought about what comes next. One AWP panel proposal I was part of made the especially harsh cut this year (23.7% acceptance rate!), so I’ll be in Baltimore in March 2026. I’m part of an arts festival at Charlottesville’s Botanical Garden of the Piedmont on September 7th, teaching a 90-minute workshop called “Listening for Poetry” (free and open to anyone, but you have to register). Next week I have a short trip to NYC to read in the Bryant Park Reading Room (Tues 8/26 6 pm). More remembrance: the previous time I appeared in the Bryant Park series was May 2012. I recall the month because I visited my dying father in the Philadelphia VA hospital on the way home–the last time I saw him. On the train I read Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars, a book about her father’s death. The event itself was joyous. Scott Hightower was there, and someone else I wish I could remember, and the fourth reader was Richard Blanco. I’d never met or heard Blanco before then, but he would go on to become Obama’s second inaugural poet. (May we please be arguing again about the merits of a US inaugural poem in 2029–only Democratic presidents have commissioned them.)

My official reason for this travel was the ASLE-UKI conference in Galway, which I enjoyed very much, but the wild places of Connemara, pictured above, will stay with me at least as long. Look at the sedimentary swirls on those beach rocks, how they were obviously part of the same stone once, a triptych! Although it’s less dramatic in a photograph, one of my favorite half-hours was a shortcut we took along Bog Road (where the rainbow sheep are snacking). I’m apparently especially inspired by stark landscapes, although remembering Seamus Heaney’s bog poems as we drove through certainly intensified the poetry of it all. One day I’ll have to visit where the Cain branch of my family is from–County Wexford, I think, before they were excommunicated for political reasons and moved to Liverpool, according to my mother’s lore. (I kind of wanted to name my kids Magdalen and Cain, doubling down on the heresy of it all, but chickened out–just as well for their fortunes in Virginia public schools.) The food in Galway is fancier than in the rural places, but I have to add that in our Connemara hotel, just south of Clifden, I ate the best, freshest, sweetest seafood of my life. Chris reports that I was murmuring “those mussels!” in my sleep.

From the conference, a few notes I took:

- From a panel about acoustic ecology, from Martin Schauss: “The Hum” that some communities report hearing (The Windsor Hum, Taos Hum, Isle of Lewis): is it geologic, manmade? Cage wrote that “traffic is the defining aesthetic experience of modern ecology.” Macfarlane refers to a “sonic undersong.” From an audience member: there is a level of hertz when you slip from the auditory to tactile. (I wonder if I love the sea or other places because their subsonics move me.)

- Across panels, lots of talk about poetry as activism, which it mostly isn’t, in my opinion. But I love something a panelist quoted from Caitríona O’Reilly about poetry “taking back your attention.” It’s hard to wrench yourself away from a cellphone, but writing and reading and listening to verbal art can be powerful practices because they require you to–radical in a different way.

- Pollution is colonialism. (Didn’t write down who said that.)

- Menopause can be a queer experience affecting gender identity, Emma Pavey theorized with lots more care than this short note reflects, and a trans audience member spoke up about taking T. (Yes, this panel was a little different, and I loved it!)

I also returned with long lists of books and articles to read. Back to it, as the peepers ring. I’ll leave you with a snippet of soundscape from Connemara.

5 responses to “Hawthorns, bogs, & undersongs”

This was lovely- thanks so much for taking time to share something so uplifting. Sent from my iPhone

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much!

LikeLike

I can relate to that sciatica, alas Enjoyed reading your Irish landscape. Wishing you Septober Energy.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I do remember those Seamus Heaney bog poems from Prof Wheeler’s freshman year seminar. Those have “stuck” all these years. Enjoyed your pictures – thank you for sharing!

LikeLiked by 2 people

They are sticky poems! So nice to hear from you, Derek.

LikeLike